Description

OCD is a condition in which a piece of bone and cartilage are at risk of loosening or dislodging from the joint (end of the bone). Weakening of the underlying bone occurs with OCD from several possible causes including blood supply problems, overuse, and genetics (sometimes these run in families). The overlying joint cartilage will often remain alive but relies on stable supporting bone. The piece of bone and cartilage that forms the OCD is like a piece of a puzzle trying to jump out. The piece can sit tight (and stable) within the puzzle, it can sit loosely (and unstable) within the puzzle, it can sit partially within the puzzle, or it can completely dislodge. Treatment depends on the age of the patient and the stability (looseness) of the OCD. Younger patients who are still growing tend to heal these much better than older patients who have stopped growing. OCDs that are stable do better than those that are unstable. These OCD lesions happen most commonly in the knee, elbow, and ankle. Elbow OCD happens most frequently in throwing athletes and gymnasts.

Symptoms

It is not well understood whether OCD is always painful. Sometimes the loose, unstable OCDs will cause swelling, popping, catching and pain. Frequently, however, these are discovered as “incidental findings,” which means that your doctor was looking into another problem.

Examination

Your doctor will check the joint for motion, swelling, and catching. If it is a knee or ankle OCD, walking will also be evaluated.

X-Rays and Tests

Your doctor will often start with x-rays. In the knee, if there is no swelling in the joint or signs of the fragment separating, growing patients may not require further imaging or surgery. Often the cartilage is intact over the soft area of bone. In patients with other symptoms such as locking or swelling, MRI may be used to provide details of the OCD and how stable it is.

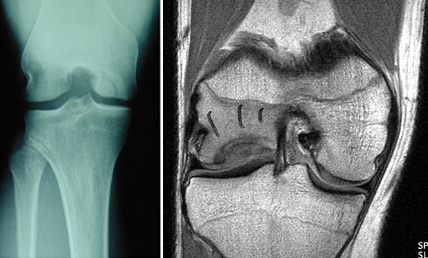

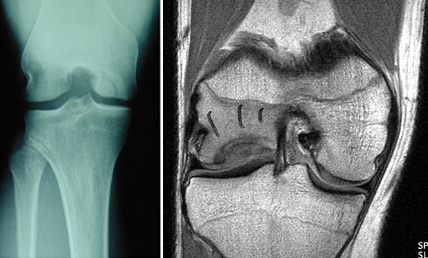

X-ray and MRI with OCD of the knee

Treatment

Younger patients will often heal these OCDs, especially if they are stable, without surgery. Rest from repetitive running and jumping can allow the weak area of bone to heal under the stable cartilage and result in a normal knee. If the patient is older and approaching the end of growth, or if the OCD is not stable, procedures may be recommended to promote healing of the soft bone to allow the overlying cartilage to remain intact and avoid fragmentation. This may range from “drilling” the OCD to promote healing to fixation of separated fragments using screws.

If the OCD is not fixable, or has too much damage to the cartilage layer to heal, your doctor may use another strategy to replace missing cartilage. This more often happens in older patients after the end of growth.

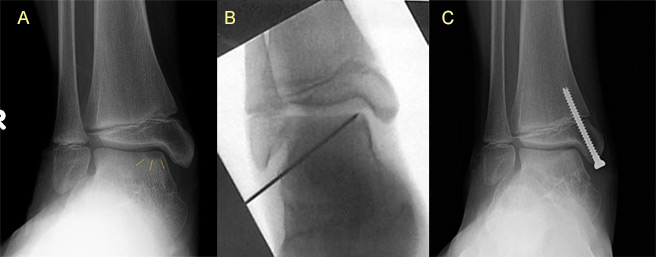

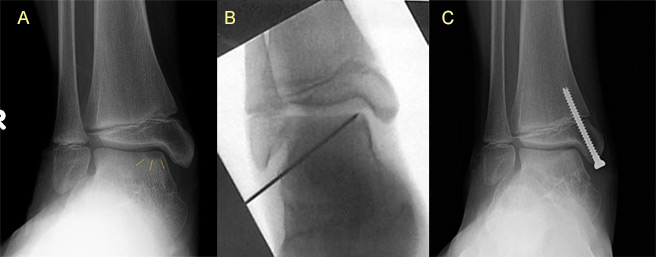

Figure 1:

Figure 1: 8 year old male with painful flatfeet and incidental finding of talar OCD. (A) X-ray; (B) Drilling of OCD to stimulate bone healing; (C) 4 months after surgery with healing of OCD and screw placed to guide growth out of flatfoot alignment.

Outcomes (Prognosis/Expectations)

In younger patients with stable OCD lesions, prognosis for healing of the OCD and return to full sports and activities in the knee and ankle is very good. In the elbow, prognosis is not as good, and throwing and gymnastics are not always possible after elbow OCD. Older patients and patients with unstable OCD have more challenges with full healing and returning to full sports participation.

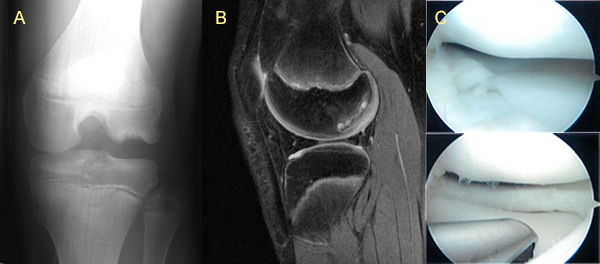

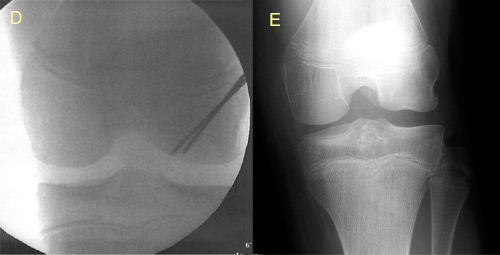

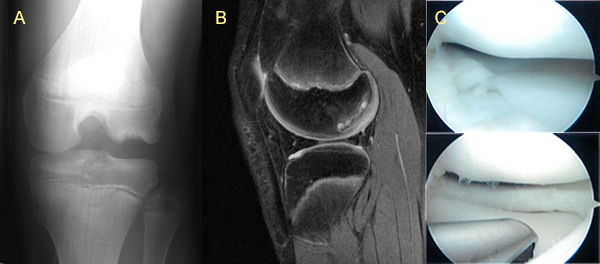

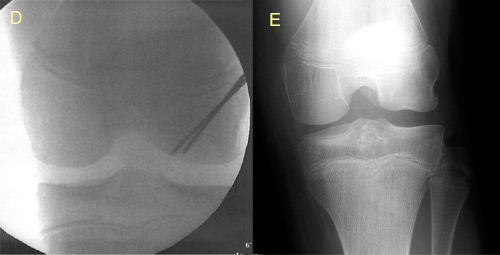

Figure 2:

Figure 2: 13 y/o basketball player presenting with knee pain. (A) X-ray with lateral femoral condyle OCD; (B) MRI with intact cartilage (and discoid meniscus); (C) Arthroscopy images showing intact cartilage (and discoid meniscus); (D) Intraoperative x-rays showing retrograde drilling of OCD; (E) X-ray demonstrating healing 6 months later.

More Information

POSNA.org

POSNA.org